History of Vietnam

| History of Vietnam |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The history of Vietnam begins around 2,700 years ago. Successive dynasties based in China ruled Vietnam directly for most of the period from 207 BC until 938 when Vietnam regained its independence.[1] Vietnam remained a tributary state to its larger neighbor China for much of its history but repelled invasions by the Chinese as well as three invasions by the Mongols between 1255 and 1285.[2] Emperor Trần Nhân Tông later diplomatically submitted Vietnam to a tributary of the Yuan to avoid further conflicts. The independent period temporarily ended in the middle to late 19th century, when the country was colonized by France (see French Indochina). During World War II, Imperial Japan expelled the French to occupy Vietnam, though they retained French administrators during their occupation. After the war, France attempted to re-establish its colonial rule but ultimately failed in the First Indochina War. The Geneva Accords partitioned the country in two with a promise of democratic election to reunite the country.

However, rather than peaceful reunification, partition led to the Vietnam War. During this time, the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union supported the North while the United States supported the South. After millions of Vietnamese deaths, the war ended with the fall of Saigon to the North in April 1975. The reunified Vietnam suffered further internal repression and was isolated internationally due to the continuing Cold War and the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. In 1986, the Communist Party of Vietnam changed its economic policy and began reforms of the private sector similar to those in China. Since the mid-1980s, Vietnam has enjoyed substantial economic growth and some reduction in political repression, though reports of corruption have also risen.

Early kingdoms

Evidence of the earliest established society other than the prehistoric Iron Age Đông Sơn culture in Northern Vietnam was found in Cổ Loa, an ancient city situated near present-day Hà Nội.

According to myth, the first Vietnamese people were descended from the Dragon Lord Lạc Long Quân and the Immortal Fairy Âu Cơ. Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ had 100 sons before deciding to part ways. 50 of the children went with their mother to the mountains, and the other 50 went with their father to the sea. The eldest son became the first in a line of early Vietnamese kings, collectively known as the Hùng kings (Hùng Vương or the Hồng Bàng Dynasty). The Hùng kings called their country, located on the Red River delta in present-day northern Vietnam, Văn Lang. The people of Văn Lang were known as the Lạc Việt.

Văn Lang is thought to have been a matriarchal society, similar to many other matriarchal societies common in Southeast Asia and in the Pacific islands at the time. Various archaeological sites in northern Vietnam, such as Đông Sơn have yielded metal weapons and tools from this age. Most famous of these artifacts are large bronze drums, probably made for ceremonial purposes, with sophisticated engravings on the surface, depicting life scenes with warriors, boats, houses, birds and animals in concentric circles around a radiating sun at the center.

Many legends from this period offer a glimpse into the life of the people. The Legend of the Rice Cakes is about a prince who won a culinary contest; he then wins the throne because his creations, the rice cakes, reflect his deep understanding of the land's vital economy: rice farming. The Legend of Giong about a youth going to war to save the country, wearing iron armor, riding an armored horse, and wielding an iron staff, showed that metalworking was sophisticated. The Legend of the Magic Crossbow, about a crossbow that can deliver thousands of arrows, showed extensive use of archery in warfare.

Recent research has unlocked the discovery of artificial circular earthworks in the areas of present day southern Vietnam and overlapping to the borders of Cambodia. These archaeological remains are estimated to be economic, social and cultural entities from the 1st millennium BC[3]

By the 3rd century BC, another Viet group, the Âu Việt, emigrated from present-day southern China to the Red River delta and mixed with the indigenous Văn Lang population. In 258 BC, a new kingdom, Âu Lạc, emerged as the union of the Âu Việt and the Lạc Việt, with Thục Phán proclaiming himself "King An Dương Vương". At his capital Cổ Loa, he built many concentric walls around the city for defensive purposes. These walls, together with skilled Âu Lạc archers, kept the capital safe from invaders for a while. However, it also gave rise to the first recorded case of espionage in Vietnamese history, resulting in the downfall of King An Dương Vương.

In 207 BC, an ambitious Chinese warlord named Triệu Đà (Chinese: Zhao Tuo) defeated King An Dương Vương by having his son Trọng Thủy (Chinese: Zhong Shi) act as a spy after marrying An Dương Vương's daughter. Triệu Đà annexed Âu Lạc into his domain located in present-day Guangdong, southern China, then proclaimed himself king of a new independent kingdom, Nam Việt (Chinese: 南越, Nan Yue). Trọng Thủy, the supposed crown prince, drowned himself in Cổ Loa out of remorse for the death of his wife in the war.

Some Vietnamese consider Triệu's rule a period of Chinese domination, since Triệu Đà was a former Qin general. Others consider it an era of Việt independence as the Triệu family in Nam Việt were assimilated to local culture. They ruled independently of what then constituted China's (Han Dynasty). At one point, Triệu Đà even declared himself Emperor, equal to the Chinese Han Emperor in the north.

Period of Chinese domination (111 BC – 938 AD)

In 111 BC, Chinese troops invaded Nam Việt and established new territories, dividing Vietnam into Giao Chỉ (Chinese: 交趾 pinyin: Jiaozhi, now the Red River delta); Cửu Chân from modern-day Thanh Hoá to Hà Tĩnh; and Nhật Nam, from modern-day Quảng Bình to Huế. While the Chinese were governors and top officials, the original Vietnamese nobles (Lạc Hầu, Lạc Tướng) still managed some highlands.

In 40 AD, a successful revolt against harsh rule by Han Governor Tô Định (蘇定 pinyin: Sū Dìng), led by the noblewoman Trưng Trắc and her sister Trưng Nhị, recaptured 65 states (include modern Guangxi), and Trưng Trắc became the Queen (Trưng Nữ Vương). In 42 AD, Emperor Guangwu of Han sent his famous general Mã Viện (Chinese: Ma Yuan) to quell the revolt. After a torturous campaign, Ma Yuan defeated the Trưng Queen, who committed suicide. To this day, the Trưng Sisters are revered in Vietnam as the national symbol of Vietnamese women. Learning a lesson from the Trưng revolt, the Han and other successful Chinese dynasties took measures to eliminate the power of the Vietnamese nobles. The Vietnamese elites would be coerced to assimilate into Chinese culture and politics. However, in 225 AD, another woman, Triệu Thị Trinh, popularly known as Lady Triệu (Bà Triệu), led another revolt which lasted until 248 AD.

During the Tang dynasty, Vietnam was called Annam (Giao Châu), until the early 10th century AD. Giao Chỉ (with its capital around modern Bắc Ninh province) became a flourishing trading outpost receiving goods from the southern seas. The "History of Later Han" (Hậu Hán Thư, Hou Hanshu) recorded that in 166 AD the first envoy from the Roman Empire to China arrived by this route, and merchants were soon to follow. The 3rd-century "Tales of Wei" (Ngụy Lục, Weilue) mentioned a "water route" (the Red River) from Jiaozhi into what is now southern Yunnan. From there, goods were taken overland to the rest of China via the regions of modern Kunming and Chengdu.

At the same time, in present-day central Vietnam, there was a successful revolt of Cham nations. Chinese dynasties called it Lin-Yi (Lin village). It later became a powerful kingdom, Champa, stretching from Quảng Bình to Phan Thiết (Bình Thuận).

In the period between the beginning of the Chinese Age of Fragmentation to the end of the Tang Dynasty, several revolts against Chinese rule took place, such as those of Lý Bôn and his general and heir Triệu Quang Phục; and those of Mai Thúc Loan and Phùng Hưng. All of them ultimately failed, yet most notable were Lý Bôn and Triệu Quang Phục, whose Anterior Lý Dynasty ruled for almost half a century (544 AD to 602 AD) before the Chinese Sui Dynasty reconquered their kingdom Vạn Xuân.

Early independence (938 AD – 1009 AD)

Early in the 10th century, as China became politically fragmented, successive lords from the Khúc family, followed by Dương Đình Nghệ, ruled Giao Châu autonomously under the Tang title of Tiết Độ Sứ, Virtuous Lord, but stopping short of proclaiming themselves kings.

In 938, Southern Han sent troops to conquer autonomous Giao Châu. Ngô Quyền, Dương Đình Nghệ's son-in-law, defeated the Southern Han fleet at the Battle of Bạch Đằng River (938). He then proclaimed himself King Ngô and effectively began the age of independence for Vietnam.

Ngô Quyền's untimely death after a short reign resulted in a power struggle for the throne, the country's first major civil war, The upheavals of Twelve warlords (Loạn Thập Nhị Sứ Quân). The war lasted from 945 AD to 967 AD when the clan led by Đinh Bộ Lĩnh defeated the other warlords, unifying the country. Dinh founded the Đinh Dynasty and proclaimed himself First Emperor (Tiên Hoàng) of Đại Cồ Việt (Hán tự: 大瞿越; literally "Great Viet Land"), with its capital in Hoa Lư (modern day Ninh Bình). However, the Chinese Song Dynasty only officially recognized him as Prince of Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ Quận Vương). Emperor Đinh introduced strict penal codes to prevent chaos from happening again. He tried to form alliances by granting the title of Queen to five women from the five most influential families.

In 979 AD, Emperor Đinh Bộ Lĩnh and his crown prince Đinh Liễn were assassinated, leaving his lone surviving son, the 6-year-old Đinh Toàn, to assume the throne. Taking advantage of the situation, the Chinese Song Dynasty invaded Đại Cồ Việt. Facing such a grave threat to national independence, the court's Commander of the Ten Armies (Thập Đạo Tướng Quân) Lê Hoàn took the throne, founding the Former Lê Dynasty. A capable military tactician, Lê Hoan realized the risks of engaging the mighty Chinese troops head on; thus he tricked the invading army into Chi Lăng Pass, then ambushed and killed their commander, quickly ending the threat to his young nation in 981 AD. The Song Dynasty withdrew their troops yet would not recognize Lê Hoàn as Prince of Jiaozhi until 12 years later; nevertheless, he is referred to in his realm as Đại Hành Emperor (Đại Hành Hoàng Đế). Emperor Lê Hoàn was also the first Vietnamese monarch who began the southward expansion process against the kingdom of Champa.

Emperor Lê Hoàn's death in 1005 AD resulted in infighting for the throne amongst his sons. The eventual winner, Lê Long Đĩnh, became the most notorious tyrant in Vietnamese history. He devised sadistic punishments of prisoners for his own entertainment and indulged in deviant sexual activities. Toward the end of his short life – he died at 24 – Lê Long Đĩnh became so ill that he had to lie down when meeting with his officials in court.

Independent period of Đại Việt (1010 AD – 1527 AD)

When the king Lê Long Đĩnh died in 1009 AD, a Palace Guard Commander named Lý Công Uẩn was nominated by the court to take over the throne, and founded the Lý dynasty. This event is regarded as the beginning of a golden era in Vietnamese history, with great following dynasties. The way Lý Công Uẩn ascended to the throne was rather uncommon in Vietnamese history. As a high-ranking military commander residing in the capital, he had all opportunities to seize power during the tumultuous years after Emperor Lê Hoàn's death, yet preferring not to do so out of his sense of duty. He was in a way being "elected" by the court after some debate before a consensus was reached.

Lý Công Uẩn, posthumously referred as Lý Thái Tổ, changed the country's name to Đại Việt (Hán tự: 大越; literally "Great Viet"). The Lý Dynasty is credited for laying down a concrete foundation, with strategic vision, for the nation of Vietnam. Leaving Hoa Lư, a natural fortification surrounded by mountains and rivers, Lý Công Uẩn moved his court to the new capital in present-day Hanoi and called it Thăng Long (Ascending Dragon). Lý Công Uẩn thus departed from the militarily defensive mentality of his predecessors and envisioned a strong economy as the key to national survival. Successive Lý kings continued to accomplish far-reaching feats: building a dike system to protect the rice producing area; founding Quốc Tử Giám, the first noble university; holding regular examinations to select capable commoners for government positions once every three years; organizing a new system of taxation; establishing humane treatment of prisoners. Women were holding important roles in Lý society as the court ladies were in charge of tax collection. The Lý Dynasty also promoted Buddhism, yet maintained a pluralistic attitude toward the three main philosophical systems of the time: Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. During the Lý Dynasty, the Chinese Song Dynasty officially recognized the Đại Việt monarch as King of Giao Chỉ (Giao Chỉ Quận Vương).

The Lý Dynasty had two major wars with Song China, and a few conquests against neighboring Champa in the south. The most notable battle took place on Chinese territory in 1075 AD. Upon learning that a Song invasion was imminent, the Lý army and navy totalling about 100,000 men under the command of Lý Thường Kiệt, Tông Đản used amphibious operations to preemptively destroy three Song military installations at Yong Zhou, Qin Zhou, and Lian Zhou in present-day Guangdong and Guangxi, and killed 100,000 Chinese. The Song Dynasty took revenge and invaded Đại Việt in 1076, but the Song troops were held back at the Battle of Như Nguyệt River commonly known as the Cầu river, now in Bắc Ninh province about 40 km from the current capital, Hanoi. Neither side was able to force a victory, so the Lý Dynasty proposed a truce, which the Song Dynasty accepted.

Toward the end of the Lý Dynasty, a powerful court minister named Trần Thủ Độ forced king Lý Huệ Tông to become a Buddhist monk and Lý Chiêu Hoàng, Huệ Tông's young daughter, to become queen. Trần Thủ Độ then arranged the marriage of Chiêu Hoàng to his nephew Trần Cảnh and eventually had the throne transferred to Trần Cảnh, thus begun the Trần Dynasty. Trần Thủ Độ viciously purged members of the Lý nobility; some Lý princes escaped to Korea, including Lý Long Tường.

After the purge most Trần kings ruled the country in similar manner to the Lý kings. Noted Trần Dynasty accomplishments include the creation of a system of population records based at the village level, the compilation of a formal 30-volume history of Đại Việt (Đại Việt Sử Ký) by Lê Văn Hưu, and the rising in status of the Nôm script, a system of writing for Vietnamese language. The Trần Dynasty also adopted a unique way to train new kings: as a king aged, he would relinquish the throne to his crown prince, yet holding a title of August Higher Emperor (Thái Thượng Hoàng), acting as a mentor to the new Emperor.

Mongol invasions

During the Trần Dynasty, the armies of the Mongol Empire under Mongke Khan and Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty invaded Vietnam in 1257 AD, 1284 AD, and 1288 AD. Đại Việt repelled all attacks of the Yuan during the reign of Kublai Khan. The key to Đại Việt's successes was to avoid the Mongols' strength in open field battles and city sieges - the Trần court abandoned the capital and the cities. The Mongols were then countered decisively at their weak points, which were battles in swampy areas such as Chương Dương, Hàm Tử, Vạn Kiếp and on rivers such as Vân Đồn and Bạch Đằng. The Mongols also suffered from tropical diseases and loss of supplies to Trần army's raids. The Yuan-Trần war reached its climax when the retreating Yuan fleet was decimated at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288). The military architect behind Đại Việt's victories was Commander Trần Quốc Tuấn, more popularly known as Trần Hưng Đạo. In order to avoid disastrous campaigns, the Tran and Champa acknowledged Mongol supremacy.

Champa

It was also during this period that the Trần kings waged many wars against the southern kingdom of Champa, continuing the Viets' long history of southern expansion (known as Nam Tiến) that had begun shortly after gaining independence from China. Often, they encountered strong resistance from the Chams. Champa troops led by king Chế Bồng Nga (Cham: Po Binasuor or Che Bonguar) killed king Trần Duệ Tông in battle and even laid siege to Đại Việt's capital Thăng Long in 1377 AD and again in 1383 AD. However, the Trần Dynasty was successful in gaining two Champa provinces, located around present-day Huế, through the peaceful means of the political marriage of Princess Huyền Trân to a Cham king.

Ming occupation and the rise of the Lê Dynasty

The Trần dynasty was in turn overthrown by one of its own court officials, Hồ Quý Ly. Hồ Quý Ly forced the last Trần king to resign and assumed the throne in 1400. He changed the country name to Đại Ngu (Hán tự: 太虞) and moved the capital to Tây Đô, Western Capital, now Thanh Hóa. Thăng Long was renamed Đông Đô, Eastern Capital. Although widely blamed for causing national disunity and losing the country later to the Chinese Ming Dynasty, Hồ Quý Ly's reign actually introduced a lot of progressive, ambitious reforms, including the addition of mathematics to the national examinations, the open critique of Confucian philosophy, the use of paper currency in place of coins, investment in building large warships and cannon, and land reform. He ceded the throne to his son, Hồ Hán Thương, in 1401 and assumed the title Thái Thượng Hoàng, in similar manner to the Trần kings.

In 1407, under the pretext of helping to restore the Trần Dynasty, Chinese Ming troops invaded Đại Ngu and captured Hồ Quý Ly and Hồ Hán Thương. The Hồ Dynasty came to an end after only 7 years in power. The Ming occupying force annexed Đại Ngu into the Ming Empire after claiming that there was no heir to Trần throne. Almost immediately, Trần loyalists started a resistance war. The resistance, under the leadership of Trần Quĩ at first gained some advances, yet as Trần Quĩ executed two top commanders out of suspicion, a rift widened within his ranks and resulted in his defeat in 1413.

In 1418, a wealthy farmer, Lê Lợi, led the Lam son revolution against the Ming from his base of Lam Sơn (Thanh Hóa province). Overcoming many early setbacks and with strategic advices from Nguyễn Trãi, Lê Lợi's movement finally gathered momentum, marched northward, and launched a siege at Đông Quan (now Hanoi), the capital of the Ming occupation. The Ming Emperor sent a reinforcement force, but Lê Lợi staged an ambush and killed the Ming commander, Liễu Thăng (Chinese: Liu Sheng), in Chi Lăng. Ming troops at Đông Quan surrendered. The Lam son revolution killed 300,000 Ming soldiers. In 1428, Lê Lợi ascended to the throne and began the Hậu Lê dynasty (Posterior or Later Lê). Lê Lợi renamed the country back to Đại Việt and moved the capital back to Thăng Long.

The Lê Dynasty carried out land reforms to revitalize the economy after the war. Unlike the Lý and Trần kings, who were more influenced by Buddhism, the Lê kings leaned toward Confucianism. A comprehensive set of laws, the Hồng Đức code was introduced with some strong Confucian elements, yet also included some progressive rules, such as the rights of women. Art and architecture during the Lê Dynasty also became more influenced by Chinese styles than during the Lý and Trần Dynasty. The Lê Dynasty commissioned the drawing of national maps and had Ngô Sĩ Liên continue the task of writing Đại Việt's history up to the time of Lê Lợi. King Lê Thánh Tông opened hospitals and had officials distribute medicines to areas affected with epidemics.

In 1471, Le troops led by king Lê Thánh Tông invaded Champa and captured its capital Vijaya. This event effectively ended Champa as a powerful kingdom, although some smaller surviving Cham kingdoms still lasted for a few centuries more. It initiated the dispersal of the Cham people across Southeast Asia. With the kingdom of Champa mostly destroyed and the Cham people exiled or suppressed, Vietnamese colonization of what is now central Vietnam proceeded without substantial resistance. However, despite becoming greatly outnumbered by Kinh (Việt) settlers and the integration of formerly Cham territory into the Vietnamese nation, the majority of Cham people nevertheless remained in Vietnam and they are now considered one of the key minorities in modern Vietnam. The city of Huế, founded in 1600 lies close to where the Champa capital of Indrapura once stood. In 1479, King Lê Thánh Tông also campaigned against Laos and captured its capital Luang Prabang. He made further incursions westwards into the Irrawaddy River region in modern-day Burma before withdrawing.

Divided period (1528–1802)

The Lê dynasty was overthrown by its general named Mạc Đăng Dung in 1527. He killed the Lê emperor and proclaimed himself emperor, starting the Mạc Dynasty. After defeating many revolutions for two years, Mạc Đăng Dung adopted the Trần Dynasty's practice and ceded the throne to his son, Mạc Đăng Doanh, who became Thái Thượng Hoàng.

Meanwhile, Nguyễn Kim, a former official in the Lê court, revolted against the Mạc and helped king Lê Trang Tông restore the Lê court in the Thanh Hóa area. Thus a civil war began between the Northern Court (Mạc) and the Southern Court (Restored Lê). Nguyễn Kim's side controlled the southern part of Đại Việt (from Thanhhoa to the south), leaving the north (including Đông Kinh-Hanoi) under Mạc control. When Nguyễn Kim was assassinated in 1545, military power fell into the hands of his son-in-law, Trịnh Kiểm. In 1558, Nguyễn Kim's son, Nguyễn Hoàng, suspecting that Trịnh Kiểm might kill him as he had done to his brother to secure power, asked to be governor of the far south provinces around present-day Quảng Bình to Bình Định. Hoang pretended to be insane, so Kiem was fooled into thinking that sending Hoang south was a good move as Hoang would be quickly killed in the lawless border regions. However, Hoang governed the south effectively while Trịnh Kiểm, and then his son Trịnh Tùng, carried on the war against the Mạc. Nguyễn Hoàng sent money and soldiers north to help the war but gradually he became more and more independent, transforming their realm's economic fortunes by turning it into an international trading post.

The civil war between the Lê/Trịnh and Mạc dynasties ended in 1592, when the army of Trịnh Tùng conquered Hanoi and executed king Mạc Mậu Hợp. Survivors of the Mạc royal family fled to the northern mountains in the province of Cao Bằng and continued to rule there until 1667 when Trịnh Tạc conquered this last Mạc territory. The Lê kings, ever since Nguyễn Kim's restoration, only acted as figureheads. After the fall of the Mạc Dynasty, all real power in the north belonged to the Trịnh Lords.

In the year 1600, Nguyễn Hoàng also declared himself Lord (officially "Vương", popularly "Chúa") and refused to send more money or soldiers to help the Trịnh. He also moved his capital to Phú Xuân, modern-day Huế. Nguyễn Hoàng died in 1613 after having ruled the south for 55 years. He was succeeded by his 6th son, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, who likewise refused to acknowledge the power of the Trịnh, yet still pledged allegiance to the Lê king.

Trịnh Tráng succeeded Trịnh Tùng, his father, upon his death in 1623. Tráng ordered Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên to submit to his authority. The order was refused twice. In 1627, Trịnh Tráng sent 150,000 troops southward in an unsuccessful military campaign. The Trịnh were much stronger, with a larger population, economy and army, but they were unable to vanquish the Nguyễn, who had built two defensive stone walls and invested in Portuguese artillery.

The Trịnh-Nguyễn War lasted from 1627 until 1672. The Trịnh army staged at least seven offensives, all of which failed to capture Phú Xuân. For a time, starting in 1651, the Nguyễn themselves went on the offensive and attacked parts of Trịnh territory. However, the Trịnh, under a new leader, Trịnh Tạc, forced the Nguyễn back by 1655. After one last offensive in 1672, Trịnh Tạc agreed to a truce with the Nguyễn Lord Nguyễn Phúc Tần. The country was effectively divided in two.

The Trịnh and the Nguyễn maintained a relative peace for the next hundred years, during which both sides made significant accomplishments. The Trịnh created centralized government offices in charge of state budget and producing currency, unified the weight units into a decimal system, established printing shops to reduce the need to import printed materials from China, opened a military academy, and compiled history books.

Meanwhile, the Nguyễn Lords continued the southward expansion by the conquest of the remaining Cham land. Việt settlers also arrived in the sparsely populated area known as "Water Chenla", which was the lower Mekong Delta portion of Chenla (present-day Cambodia). Between the mid-17th century to mid-18th century, as Chenla was weakened by internal strife and Siamese invasions, the Nguyễn Lords used various means, political marriage, diplomatic pressure, political and military favors,... to gain the area around present day Saigon and the Mekong Delta. The Nguyễn army at times also clashed with the Siamese army to establish influence over Chenla.

In 1771, the Tây Sơn revolution broke out in Quynhơn, which was under the control of the Nguyễn. The leaders of this revolution were three brothers named Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ, and Nguyễn Huệ, not related to the Nguyễn lords. By 1776, the Tây Sơn had occupied all of the Nguyễn Lord's land and killed almost the entire royal family. The surviving prince Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (often called Nguyễn Ánh) fled to Siam, and obtained military support from the Siamese king. Nguyễn Ánh came back with 50000 Siamese troops to regain power, but was defeated at the Battle of Rạch Gầm–Xoài Mút and almost killed. Nguyễn Ánh fled Vietnam, but he did not give up.

The Tây Sơn army commanded by Nguyễn Huệ marched north in 1786 to fight the Trịnh Lord, Trịnh Khải. The Trịnh army failed and Trịnh Khải committed suicide. The Tây Sơn army captured the capital in less than two months. The last Lê emperor, Lê Chiêu Thống, fled to China and petitioned the Chinese Qing Emperor for help. The Qing emperor Qianlong supplied Lê Chiêu Thống with a massive army of around 200,000 troops to regain his throne from the usurper. Nguyễn Huệ proclaimed himself Emperor Quang Trung and defeated the Qing troops with 100,000 men in a surprise 7 day campaign during the lunar new year (Tết). During his reign, Quang Trung envisioned many reforms but died by unknown reason on the way march south in 1792, at the age of 40.

During the reign of Emperor Quang Trung, Đại Việt was actually divided into 3 political entities. The Tây Sơn leader, Nguyễn Nhạc, ruled the centre of the country from his capital Qui Nhơn. Emperor Quang Trung ruled the north from the capital Phú Xuân Huế. In the South, Nguyễn Ánh, assisted by many talented recruits from the South, captured Gia Định (present day Saigon) in 1788 and established a strong base for his force.

After Quang Trung's death, the Tây Sơn Dynasty became unstable as the remaining brothers fought against each other and against the people who were loyal to Nguyễn Huệ's infant son. Nguyễn Ánh sailed north in 1799, capturing Tây Sơn's stronghold Qui Nhơn. In 1801, his force took Phú Xuân, the Tây Sơn capital. Nguyễn Ánh finally won the war in 1802, when he sieged Thăng Long (Hanoi) and executed Nguyễn Huệ's son, Nguyễn Quang Toản, along with many Tây Sơn generals and officials. Nguyễn Ánh ascended the throne and called himself Emperor Gia Long. Gia is for Gia Định, the old name of Saigon; Long is for Thăng Long, the old name of Hanoi. Hence Gia Long implied the unification of the country. The Nguyễn dynasty lasted until Bảo Đại's abdication in 1945. As China for centuries had referred to Đại Việt as Annam, Gia Long asked the Chinese Qing emperor to rename the country, from Annam to Nam Việt. To prevent any confusion of Gia Long's kingdom with Triệu Đà's ancient kingdom, the Chinese emperor reversed the order of the two words to Việt Nam. The name Vietnam is thus known to be used since Emperor Gia Long's reign. Recently historians have found that this name had existed in older books in which Vietnamese referred to their country as Vietnam.

The Period of Division with its many tragedies and dramatic historical developments inspired many poets and gave rise to some Vietnamese masterpieces in verse such as the epic poem The Tale of Kieu (Truyện Kiều) by Nguyễn Du, Song of a Soldier's Wife (Chinh Phụ Ngâm) by Đặng Trần Côn and Đoàn Thị Điểm, and a collection of satirical, erotically charged poems by the female poet Hồ Xuân Hương.

19th century and French colonization

The West's exposure in Vietnam and Vietnam's exposure to Westerners dated back to 166 BC with the arrival of merchants from the Roman Empire, to 1292 with the visit of Marco Polo, and the early 1500s with the arrival of Portuguese and other European traders and missionaries. Alexandre de Rhodes, a French Jesuit priest, improved on earlier work by Portuguese missionaries and developed the Vietnamese romanized alphabet Quốc Ngữ in Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanam et Latinum in 1651.[4]

Between 1627 and 1775, two powerful families had partitioned the country: the Nguyễn Lords ruled the South and the Trịnh Lords ruled the North. The Trịnh-Nguyễn War gave European traders the opportunities to support each side with weapons and technology: the Portuguese assisted the Nguyễnin the South while the Dutch helped the Trịnh in the North.

In 1784, during the conflict between Nguyễn Ánh, the surviving heir of the Nguyễn Lords, and the Tây Sơn Dynasty, a French Catholic Bishop, Pigneaux de Behaine, sailed to France to seek military backing for Nguyễn Ánh. At Louis XVI's court, Pigneaux brokered the Little Treaty of Versailles which promised French military aid in return for Vietnamese concessions. The French Revolution broke out and Pigneaux's plan failed to materialize. Undaunted, Pigneaux went to the French territory of Pondicherry, India. He secured two ships, a regiment of Indian troops, and a handful of volunteers and returned to Vietnam in 1788. One of Pigneaux's volunteers, Jean-Marie Dayot, reorganized Nguyễn Ánh's navy along European lines and defeated the Tây Sơn at Qui Nhơn in 1792. A few years later, Nguyễn Ánh's forces captured Saigon, where Pigneaux died in 1799. Another volunteer, Victor Olivier de Puymanel would later build the Gia Định fort in central Saigon.

After Nguyễn Ánh established the Nguyễn Dynasty in 1802, he tolerated Catholicism and employed some Europeans in his court as advisors. However, he and his successors were conservative Confucians who resisted Westernization. The next Nguyễn emperors, Ming Mạng, Thiệu Trị, and Tự Đức brutally suppressed Catholicism and pursued a 'closed door' policy, perceiving the Westerners as a threat, following events such as the Lê Văn Khôi revolt when a French missionary Joseph Marchand encouraged local Catholics to revolt in an attempt to install a Catholic emperor. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese and foreign-born Christians were persecuted and trade with the West slowed during this period. There were frequent uprisings against the Nguyễns, with hundreds of such events being recorded in the annals. These acts were soon being used as excuses for France to invade Vietnam. The early Nguyễn Dynasty had engaged in many of the constructive activities of its predecessors, building roads, digging canals, issuing a legal code, holding examinations, sponsoring care facilities for the sick, compiling maps and history books, and exerting influence over Cambodia and Laos. However, those feats were not enough of an improvement in the new age of science, technology, industrialization, and international trade and politics, especially when faced with technologically superior European forces exerting strong influence over the region. The Nguyễn Dynasty is usually blamed for failing to modernize the country in time to prevent French colonization in the late 19th century.

French invasion

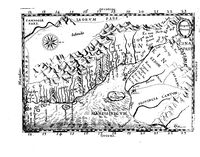

Under the orders of Napoleon III of France, French gunships under Rigault de Genouilly attacked the port of Đà Nẵng in 1858, causing significant damage, yet failed to gain any foothold, in the process being afflicted by the humidity and tropical diseases. De Genouilly decided to sail south and captured the poorly defended city of Gia Định (present-day Ho Chi Minh City). From 1859 to 1867, French troops expanded their control over all six provinces on the Mekong delta and formed a colony known as Cochin China. A few years later, French troops landed in northern Vietnam (which they called Tonkin) and captured Hà Nội twice in 1873 and 1882. The French managed to keep their grip on Tonkin although, twice, their top commanders Francis Garnier and Henri Rivière, were ambushed and killed. France assumed control over the whole of Vietnam after the Sino-French War (1884–1885). French Indochina was formed in October 1887 from Annam (Trung Kỳ, central Vietnam), Tonkin (Bắc Kỳ, northern Vietnam), Cochin China (Nam Kỳ, southern Vietnam, and Cambodia, with Laos added in 1893). Within French Indochina, Cochin China had the status of a colony, Annam was nominally a protectorate where the Nguyễn Dynasty still ruled, and Tonkin had a French governor with local governments run by Vietnamese officials.

After Gia Định fell to French troops, many Vietnamese resistance movements broke out in occupied areas, some led by former court officers, such as Trương Định, some by peasants, such as Nguyễn Trung Trực, who sank the French gunship L'Esperance using guerilla tactics. In the north, most movements were led by former court officers and lasted decades, with Phan Đình Phùng fighting in central Vietnam until 1895. In the northern mountains, the former bandit leader Hoàng Hoa Thám fought until 1911. Even the teenage Nguyễn Emperor Hàm Nghi left the Imperial Palace of Huế in 1885 with regent Tôn Thất Thuyết and started the Cần Vương, or "Save the King", movement, trying to rally the people to resist the French. He was captured in 1888 and exiled to French Algeria. Decades later, two more Nguyễn kings, Thành Thái and Duy Tân were also exiled to Africa for having anti-French tendencies. The former was deposed on the pretext of insanity and Duy Tân was caught in a conspiracy with the mandarin Tran Cao Van trying to start an uprising.

20th century

In the early 20th century, Vietnamese patriots realized that they could not defeat France without modernization. Having been exposed to Western philosophy, they aimed to establish a republic upon independence, departing from the royalist sentiments of the Cần Vương movements. Japan's defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War served as a perfect example of modernization helping an Asian country defeat a powerful European empire.

There emerged two parallel movements of modernization. The first was the Đông Du ("Go East") Movement started in 1905 by Phan Bội Châu. Châu's plan was to send Vietnamese students to Japan to learn modern skills, so that in the future they could lead a successful armed revolt against the French. With Prince Cường Để, he started two organizations in Japan: Duy Tân Hội and Việt Nam Công Hiến Hội. Due to French diplomatic pressure, Japan later deported Châu to China.

Phan Chu Trinh, who favored a peaceful, non-violent struggle to gain independence, led the second movement Duy Tân ("Modernization"). He stressed the need to educate the masses, modernize the country, foster understanding and tolerance between the French and the Vietnamese, and a peaceful transition of power.

The early part of the 20th century also saw the growing in status of the Romanized Quốc Ngữ alphabet for the Vietnamese language. Vietnamese patriots realized the potential of Quốc Ngữ as a useful tool to quickly reduce illiteracy and to educate the masses. The traditional Chinese scripts or the Nôm script were seen as too cumbersome and too difficult to learn. The use of prose in literature also became popular with the appearance of many novels; most famous were those from the literary circle Tự Lực Văn Đoàn.

As the French suppressed both movements, and after witnessing revolutionaries in action in China and Russia, Vietnamese revolutionaries began to turn to more radical paths. Phan Bội Châu created the Viet Nam Quang Phuc Hoi in Guangzhou, planning armed resistance against the French. In 1925, French agents captured him in Shanghai and spirited him to Vietnam. Due to his popularity, Châu was spared from execution and placed under house arrest until his death in 1940. In 1927, the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (Vietnamese Nationalist Party), modeled after the Kuomintang in China, was founded. In 1930, the party launched the armed Yen Bai mutiny in Tonkin which resulted in its chairman, Nguyen Thai Hoc and many other leaders captured and executed by the guillotine.

Marxism was also introduced into Vietnam with the emergence of three separate Communist parties; the Indochinese Communist Party, Annamese Communist Party and the Indochinese Communist Union, joined later by a Trotskyist movement led by Tạ Thu Thâu. In 1930 the Communist International (Comintern) sent Nguyễn Ái Quốc to Hong Kong to coordinate the unification of the parties into the Vietnamese Communist Party with Trần Phú as the first Secretary General. Later the party changed its name to the Indochinese Communist Party as the Comintern, under Stalin, did not favor nationalistic sentiments. Nguyễn Ái Quốc was a leftist revolutionary living in France since 1911. He participated in founding the French Communist Party and in 1924 traveled to the Soviet Union to join the Comintern. Through the late 1920s, he acted as a Comintern agent to help build Communist movements in Southeast Asia. During the 1930s, the Vietnamese Communist Party was nearly wiped out under French suppression with the execution of top leaders such as Phú, Lê Hồng Phong, and Nguyễn Văn Cừ.

In 1940, during World War II, Japan invaded Indochina, keeping the Vichy French colonial administration in place as a Japanese puppet. In 1941 Nguyễn Ái Quốc, now known as Hồ Chí Minh, arrived in northern Vietnam to form the Việt Minh Front, short for Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội (League for the Independence of Vietnam). The Việt Minh Front was supposed to be an umbrella group for all parties fighting for Vietnam's independence, but was dominated by the Communist Party. The Việt Minh had a modest armed force and during the war worked with the American Office of Strategic Services to collect intelligence on the Japanese. From China, other non-Communist Vietnamese parties also joined the Việt Minh and established armed forces with backing from the Kuomintang.

First Indochina War (1945-1954)

In 1944-1945, millions of Vietnamese people starved to death in the Japanese occupation of Vietnam.[5]

In early 1945, due to a combination of Japanese exploitation and poor weather, a famine broke out in Tonkin killing between 1 and 2 million people (out of a population of 10 million in the affected area). [6] In March 1945, Japanese occupying forces ousted the French administration in Indochina as they had been holding secret talks with the Free French. [7] Emperor Bảo Đại of the Nguyễn Dynasty nominally declared Vietnam independent, but the Japanese remained in occupation. Exploiting the administrative gap [8] that the internment of the French had created, the Viet Minh in March 1945 urged the population to ransack rice warehouses and refuse to pay their taxes. [9] Between 75 and 100 warehouses were consequently raided. [10] This rebellion against the effects of the famine and the authorities that were partially responsible for it bolstered the Viet Minh's popularity and they recruited many members during this period. [8]

When the Japanese surrendered to the Allies in August 1945 a power vacuum was created in Vietnam. Capatilizing on this, the Việt Minh launched the "August Revolution" across the country to seize government offices. Emperor Bảo Ðại abdicated on August 25, 1945, ending the Nguyễn Dynasty. On September 2, 1945 Hồ Chí Minh declared Vietnam independent under the new name of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and held the position of Chairman (Chủ Tịch).

British forces landed in southern Vietnam in October, disarming the Japanese and restoring order. The British commander in South East Asia, Lord Louis Mountbatten, sent over 20,000 troops of the 20th Indian division under General Douglas Gracey to occupy Saigon. The first soldiers arrived on 6 September and increased to full strength over the following weeks. In addition they re-armed Japanese prisoners of war known as Gremlin force. The British began to withdraw in December 1945, but this was not completed until June of the following year. The last British soldiers were killed in Vietnam in June 1946. Altogether 40 British and Indian troops were killed and over a hundred were wounded. Vietnamese casualties were 600. They were followed by French troops trying to re-establish their rule. In the north, Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang army entered Vietnam from China, also to disarm the Japanese, followed by the forces of the non-Communist Vietnamese parties, such as Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng and Việt Nam Cách Mạng Đồng Minh Hội. In 1946, Vietnam had its first National Assembly election (won by the Viet Minh in central and northern Vietnam [11] ), which drafted the first constitution, but the situation was still precarious: the French tried to regain power by force; some Cochin-Chinese politicians formed a seceding government of Cochin-China (Nam Kỳ Quốc) while the non-Communist and Communist forces were engaging each other in sporadic battle. Stalinists purged Trotskyists. Religious sects and resistance groups formed their own militias. The Communists eventually suppressed all non-Communist parties but failed to secure a peace deal with France.

In 1947 full scale war broke out between the Viet Minh and France. Realizing that colonialism was coming to an end worldwide, France fashioned a semi-independent State of Vietnam, within the French Union, with Bảo Đại as Head of State. Meanwhile, as the Communists under Mao Zedong took over China, the Viet Minh began to receive military aid from China. Beside supplying materials, Chinese cadres also pressured the Vietnamese Communist Party, then under First Secretary Trường Chinh, to emulate their brand of revolution, unleashing a purge of "bourgeois and feudal" elements from the Viet Minh ranks, carrying out a ruthless and bloody land reform campaign (Cải Cách Ruộng Đất), and denouncing "bourgeois and feudal" tendencies in arts and literature. Many true patriots and devoted Communist revolutionaries in the Viet Minh suffered mistreatment or were even executed during these movements. Many others became disenchanted and left the Viet Minh. The United States became strongly opposed to Hồ Chí Minh. In the 1950s the government of Bảo Ðại gained recognition by the United States and the United Kingdom.

The Việt Minh force grew significantly with China's assistance and in 1954, under the command of General Võ Nguyên Giáp, launched a major siege against French bases in Điện Biên Phủ. The Việt Minh force surprised Western military experts with their use of primitive means to move artillery pieces and supplies up the mountains surrounding Điện Biên Phủ, giving them a decisive advantage. On May 7, 1954, French troops at Điện Biên Phủ, under Christian de Castries, surrendered to the Viet Minh and in July 1954, the Geneva Accord was signed between France and the Viet-Minh, paving the way for the French to leave Vietnam.

Vietnam War (1954-1975)

The Geneva Conference of 1954 ended France's colonial presence in Vietnam and partitioned the country into two states at the 17th parallel pending unification on the basis of internationally supervised free elections. Ngô Ðình Diệm, a former mandarin with a strong Catholic and Confucian background, was selected as Premier of the State of Vietnam by Bảo Đại. While Diệm was trying to settle the differences between the various armed militias in the South, Bảo Ðại was persuaded to reduce his power. Diệm used a referendum in 1955 to depose Bảo Đại and declare himself President of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam). The Republic of Vietnam (RVN) was proclaimed in Saigon on October 26, 1955. The United States began to provide military and economic aid to the RVN, training RVN personnel, and sending U.S. advisors to assist in building the infrastructure for the new government.

Also in 1954, Vietminh forces took over North Vietnam according to the Geneva Accord. Two million North Vietnamese civilians emigrated to South Vietnam to avoid the imminent Communist regime. At the same time, Viet Minh armed forces from South Vietnam were also moving to North Vietnam, as dictated by the Geneva Accord. However, some high ranking Viet Minh cadres secretly remained in the South to follow the local situation closely. The most important figure among those was Lê Duẩn.

The Geneva Accord had promised elections to determine the government for a unified Vietnam. However, as only France and the Viet Minh had signed the document, the United States and Ngô Đình Diệm's government refused to abide by the agreement, fearing that Hồ Chí Minh would win the election due to his war popularity, establishing Communism in the whole of Vietnam. Ngô Đình Diệm took some strong measures to secure South Vietnam from perceived internal threats. He eliminated all private militias from the Bình Xuyên Party and the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo religious sects. In October 1955, he deposed Bao Dai and proclaimed himself President of the newly established the Republic of Vietnam, after rigging a referendum.[12][13] He repressed any political opposition, arresting the famous writer Nguyễn Tường Tam, who committed suicide while awaiting trial in jail.[14] Diệm also acted aggressively to remove Communist agents still remaining in the South. He formed the Cần Lao Nhân Vị Party, mixing Personalist philosophy with labor rhetorics, modeling its organization after the Communist Party, although it was anti-Communist and pro-Catholic. Another controversial policy was the Strategic Hamlet Program, which aimed to build fortified villages to lock out Communists. However, it was ineffective as many communists were already part of the population and visually indistinguishable. It became unpopular as it limited the villagers' freedom and altered their traditional way of life.

In 1960, at the Third Party Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party, ostensibly renamed the Labor Party since 1951, Lê Duẩn arrived from the South and strongly advocated the use of revolutionary warfare to topple Diệm's regime, unifying the country, and build Marxist-Leninist socialism. Despite some elements in the Party opposing the use of force, Lê Duẩn won the seat of First Secretary of the Party. As Hồ Chí Minh was aging, Lê Duẩn virtually took the helm of war from him. The first step of his war plan was coordinating a rural uprising in the South (Đồng Khởi) and forming the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) toward the end of 1960. The figurehead leader of the NLF was Nguyễn Hữu Thọ, a South Vietnamese lawyer, but the true leadership was the Communist Party hierarchy in South Vietnam. Arms, supplies, and troops came from North Vietnam into South Vietnam via a system of trails, named the Ho Chi Minh Trail, that branched into Laos and Cambodia before entering South Vietnam. At first, most foreign aid for North Vietnam came from China, as Lê Duẩn distanced Vietnam from the "revisionist" policy of the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev. However, under Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet Union picked up the pace of aid and provided North Vietnam with heavy weapons, such as T-54 tanks, artillery, MIG fighter planes, surface-to-air missiles, etc.

Meanwhile, in South Vietnam, although Ngô Đình Diệm personally was respected for his nationalism, he ran a nepotistic and authoritarian regime. Elections were routinely rigged and Diem discriminated in favour of minority Roman Catholics on many issues. His religious policies sparked protests from the Buddhist community after demonstrators were killed on Vesak, Buddha's birthday, in 1963 when they were protesting a ban on the Buddhist flag. This incident sparked mass protests calling for religious equality. The most famous case was of Venerable Thích Quảng Đức, who burned himself to death to protest. The images of this event made worldwide headlines and brought extreme embarrassment for Diem. The tension was not resolved, and on August 21, the ARVN Special Forces loyal to his brother and chief adviser Ngô Đình Nhu and commanded by Le Quang Tung raided Buddhist pagodas across the country, leaving a death toll estimated to range into the hundreds. In the United States, the Kennedy administration became worried that the problems of Diệm's regime were undermining the US's anti-Communist effort in Southeast Asia. On November 1, 1963, confident the US would not intervene or cut off aid as a result, South Vietnamese generals led by Dương Văn Minh engineered a coup d'état and overthrew Ngô Đình Diệm, killing both him and his brother Nhu.

Between 1963 and 1965, South Vietnam was extremely unstable as no government could keep power for long. There were more coups, often more than one every year. The Communist-run NLF expanded their operation and scored some significant military victories. In 1965, US President Lyndon Johnson sent troops to South Vietnam to secure the country and started to bomb North Vietnam, assuming that if South Vietnam fell to the Communists, other countries in the Southeast Asia would follow, in accordance with the Domino Theory. Other US allies, such as Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, and Taiwan also sent troops to South Vietnam. Although the American-led troops succeeded in containing the advance of Communist forces, the presence of foreign troops, the widespread bombing over all of Vietnam, and the social vices that mushroomed around US bases upset the sense of national pride among many Vietnamese, North and South, causing many to become sympathetic to North Vietnam and the NLF.

In 1965, Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu took power in a coup, and presided over a stable junta, and promised to hold elections under US pressure. In 1967, South Vietnam managed to conduct a National Assembly and Presidential election with Lt. General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu being elected to the Presidency, bringing the government to some level of stability. However, in 1968, the NLF launched a massive and surprise Tết Offensive (known in South Vietnam as "Biến Cố Tết Mậu Thân" or in the North as "Cuộc Tổng Tấn Công và Nổi Dậy Tết Mậu Thân"), attacking almost all major cities in South Vietnam over the Vietnamese New Year (Tết). NLF and North Vietnamese captured the city of Huế, after which many mass graves were found. Many of the executed victims had relations with the South Vietnamese government or the US (Thảm Sát Tết Mậu Thân). Over the course of the year the NLF forces were pushed out of all cities in South Vietnam and nearly decimated. In subsequent major offensives in later years, North Vietnamese regulars with artillery and tanks took over the fighting. In the months following the Tet Offensive, an American unit massacred civilian villagers, suspected to be sheltering Viet Cong guerillas, in the hamlet of My Lai in Central Vietnam, causing an uproar in protest around the world.

In 1969, Hồ Chí Minh died, leaving wishes that his body be cremated. However, the Communist Party embalmed his body for public display and built the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum on Ba Đình Square in Hà Nội, in the style of Lenin's Mausoleum in Moscow.

Although the Tết Offensive was a catastrophic military defeat for the Việt Cộng, it was a stunning political victory as it led many Americans to view the war as unwinnable. U.S. President Richard Nixon entered office with a pledge to end the war "with honor." He normalized US relations with China in 1972 and entered into détente with the USSR. Nixon thus forged a new strategy to deal with the Communist Bloc, taking advantage of the rift between China and the Soviet Union. A costly war in Vietnam begun to appear less effective for the cause of Communist containment. Nixon proposed "Vietnamization" of the war, with South Vietnamese troops taking charge of the fighting, yet still receiving American aid and, if necessary, air and naval support. The new strategy started to show some effects: in 1970, troops from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) successfully conducted raids against North Vietnamese bases in Cambodia (Cambodian Campaign); in 1971, the ARVN made an incursion into Southern Laos to cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Operation Lam Son 719, but the operation failed as most high positions captured by ARVN forces were recaptured by North Vietnamese artillery; in 1972, the ARVN successfully held the town of An Lộc against massive attacks from North Vietnamese regulars and recaptured the town of Quảng Trị near the demilitarised zone (DMZ) in the centre of the country during the Easter Offensive.

At the same time, Nixon was pressing both Hanoi and Saigon to sign the Paris Peace Agreement of 1973, for American military forces to withdraw from Vietnam. The pressure on Hanoi materialized with the Christmas Bombings in 1972. In South Vietnam, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu vocally opposed any accord with the Communists, but was threatened with withdrawal of American aid.

Despite the peace treaty, the North continued the war as had been envisioned by Lê Duẩn and the South still tried to recapture lost territories. In the U.S., Nixon resigned after the Watergate scandal. South Vietnam was seen as losing a strong backer. Under U.S. President Gerald Ford, the Democratic-controlled Congress became less willing to provide military support to South Vietnam.

In 1974, South Vietnam also fought and lost the Battle of Hoàng Sa against China over the control of the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea. Neither North Vietnam nor the U.S. interfered.

In early 1975, North Vietnamese military led by General Văn Tiến Dũng launched a massive attack against the Central Highland province of Buôn Mê Thuột. South Vietnamese troops had anticipated attack against the neighboring province of Pleiku, and were caught off guard. President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu ordered the moving of all troops from the Central Highland to the coastal areas, as with shrinking American aid, South Vietnamese forces could not afford to spread too thin. However, due to lack of experience and logistics for such a large troop movement in such a short time, the whole South Vietnamese 2nd Corps got bogged down on narrow mountain roads, flooded with thousands of civilian refugees, and was decimated by ambushes along the way. The South Vietnamese First Corp near the DMZ was cut off, received conflicting orders from Saigon on whether to fight or to retreat, and eventually collapsed. Many civilians tried to flee to Saigon via land, air, and sea routes, suffering massive casualties along the way. In early April 1975, South Vietnam set up a last ditch defense line at Xuân Lộc, under commander Lê Minh Đảo. North Vietnamese troops failed to penetrate the line and had to make a detour, which the South Vietnamese failed to stop due to lack of troops. President Nguyễn văn Thiệu resigned. Power fell to Dương Văn Minh.

Dương Văn Minh had led the coup against Diệm in 1963. By the mid 1970s, he had leaned toward the "Third Party" (Thành Phần Thứ Ba), South Vietnamese elites who favored dialogues and cooperation with the North. Communist infiltrators in the South tried to work out political deals to let Dương Văn Minh ascend to the Presidency, with the hope that he would prevent a last stand, destructive battle for Saigon. Although many South Vietnamese units were ready to defend Saigon, and the ARVN 4th Corp was still intact in the Mekong Delta, Duong Van Minh ordered a surrender on April 30, 1975, sparing Saigon from destruction. Nevertheless, the reputation of the North Vietnamese army towards perceived traitors preceded them, and hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese fled the country by all means: airplanes, helicopters, ships, fishing boats, and barges. Most were picked up by the U.S. Seventh Fleet in the South China Sea or landed in Thailand. The seaborne refugees came to be known as "boat people". In a famous case, a South Vietnamese pilot, with his wife and children aboard a small Cessna plane, miraculously landed safely without a tailhook on the aircraft carrier USS Midway.

During this period, North Vietnam was a Socialist state with a centralized command economy, an extensive security apparatus to carry out Dictatorship of the Proletariat, a powerful propaganda machine that effectively rallied the people for the Party's causes, a superb intelligence system that infiltrated South Vietnam (spies such as Pham Ngoc Thao climbed to high military government positions), and a severe suppression of political opposition. Even some decorated veterans and famed Communist cadres, such as Trần Đức Thảo, Nguyễn Hữu Đang, Trần Dần, Hoàng Minh Chính, were persecuted during the late 1950s Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm events and the 1960s Trial Against the Anti-Party Revisionists (Vụ Án Xét Lại Chống Đảng) for speaking their opinions. Nevertheless, this iron grip, together with consistent support from the Soviet Union and China, gave North Vietnam a militaristic advantage over South Vietnam. North Vietnamese leadership also had a steely determination to fight, even when facing massive casualties and destruction at their end. The young North Vietnamese were idealistically and innocently patriotic, ready to give the ultimate sacrifice for the "liberation of the South" and the "unification of the motherland".

Socialism after 1975

After April 30, 1975, unlike the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the Vietnamese communists did not commit a "bloodbath", but most government officials and military personnel were sent to reeducation camps. They were joined by influential people in the literary and religious circles, in these hard labor prison camps. The inhumane conditions and treatment in the camps caused many inmates to remain bitter towards the communists decades later.

Nevertheless, many North Vietnamese soldiers and cadres began to realize that they had been indoctrinated into thinking that the South Vietnamese people were utterly poor and exploited by the imperialists and foreign capitalists who treated them like slaves, shackling, whipping and terrorizing them with dogs. Contradictory to what they were taught, they saw an abundance of food and consumer goods, fashionable clothes, plenty of books and music; things that were hard to get in the North.

In 1976, Vietnam was officially unified and renamed Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRVN), with its capital in Hà Nội. The Vietnamese Communist Party dropped its front name "Labor Party" and changed the title of First Secretary, a term used by China, to Secretary General, used by the Soviet Union, with Lê Duẩn as Secretary General. The National Liberation Front was dissolved. The Party emphasised development of heavy industry and collectivisation of agriculture. Over the next few years, private enterprises were seized by the government and their owners were often sent to the New Economic Zones—a communist euphemism for a thick jungle—to clear land. The farmers were coerced into state-controlled cooperatives. Transportation of food and goods between provinces was deemed illegal except by the government. Within a short period of time, Vietnam was hit with severe shortage of food and basic necessities. The Mekong Delta, once a world-class rice-producing area, was threatened with famine. During the mid 1980s, inflation reached triple figures.

In foreign relations, the SRVN became increasingly aligned with the Soviet Union by joining the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), and signing a Friendship Pact, which was in fact a military alliance, with the Soviet Union. Tension between the Vietnam and China mounted along with China's rivalry with the Soviet Union and conflict erupted with Cambodia, China's ally. Vietnam was also subject to trade embargoes by the U.S. and its allies.

The SRVN government implemented a Stalinist dictatorship of the proletariat in the South as they did in the North. The network of security apparatus (Công An: literally "Public Security", a communist term for the security apparatus) controlled every aspect of people's life. Censorship was strict and ultra-conservative, with most pre-1975 works in the fields of music, art, and literature being banned. All religions had to be re-organized into state-controlled churches. Any negative comments toward the Party, the government, Uncle Ho, or anything related to Communism might earn the person the tag of Phản Động (Reactionary), with consequences ranging from being harassed by police, expelled from school or workplace, to being sent to prison. Nevertheless, the Communist authority failed to suppress the Black Market, where food, consumer goods, and banned literature could be bought at high prices. The security apparatus also failed to stop a nationwide clandestine network of people trying to escape the country. In many cases, the security officers of some whole districts were bribed and even got involved in organizing the escape schemes.

These living conditions resulted in an exodus of over a million Vietnamese secretly escaping the country either by sea or overland through Cambodia. For the people fleeing by sea, their wooden boats were often not seaworthy, were packed with people like sardines, and lacked sufficient food and water. Many were caught or shot at by the Vietnamese coast guards, many perished at sea due to boats sinking, capsizing in storms, starvation and thirst. Another major threat were the pirates in the Gulf of Siam, who viciously robbed, raped, and murdered the boat people. In many cases, they massacred the whole boat. Sometimes the women were raped for days before being sold into prostitution. The people who crossed Cambodia faced equal dangers with mine fields, and the Khmer Rouge and Khmer Serei guerillas, who also robbed, raped, and killed the refugees. Some were successful in fleeing the region and landed in numbers in Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Hong Kong, only to wind up in United Nations refugee camps. Some famous camps were Bidong in Malaysia, Galang in Indonesia, Bataan in the Philippines and Songkla in Thailand. Some managed to travel as far as northern Australia in crowded, open boats.

While most refugees were resettled to other countries within five years, others languished in these camps for over a decade. In the 1990s, refugees who could not find asylum were deported back to Vietnam. Communities of Vietnamese refugees arrived in the US, Canada, Australia, France, West Germany, and the UK. The refugees often sent relief packages packed with necessities, such as medicines and sanitary goods to their relatives in Vietnam to help them survive. Very few would send money as it would be exchanged far below market rates by the Vietnamese government.

In late 1978, following repeated raids by the Pol Pot regime's Khmer Rouge into Vietnamese territory, Vietnam sent troops to overthrow Pol Pot. The pro-Vietnamese People's Republic of Kampuchea was created with Heng Samrin as Chairman. Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge allied with non-Communist guerilla forces led by Norodom Sihanouk and Son Sann to fight against the Vietnamese forces and the new Phnom Penh regime. Some high ranking officials of the Heng Samrin regime in the early 1980s resisted Vietnamese control, resulting in a purge that removed Pen Sovan, Prime Minister and Secretary General of the Cambodian People's Revolutionary Party. The war lasted until 1989 when Vietnam withdrew its troops and handed the administration of Cambodia to the United Nations. The Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia had prevented the genocide of millions of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge.

In early 1979, China invaded Vietnam to supposedly "teach Vietnam a lesson" for the invasion of Cambodia and the supposed persecution of the ethnic Chinese minority. The Sino-Vietnamese War was brief, but casualties were high on both sides.[15]

Vietnam's third Constitution, based on that of the USSR, was written in 1980. The Communist Party was stated by the Constitution to be the only party to represent the people and to lead the country.

During the early 1980s, a number of overseas Vietnamese organizations were created with the aim of overthrowing the Vietnamese Communist government through armed struggle. Most groups attempted to infiltrate Vietnam but eventually were eliminated by Vietnamese security and armed forces.

Throughout the 1980s, Vietnam received nearly $3 billion a year in economic and military aid from the Soviet Union and conducted most of its trade with the USSR and other COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) countries. Some cadres, realizing the economic suffering of the people, began to break rules and experimented with market-oriented enterprises. Some were punished for their efforts, but years later would be hailed as visionary pioneers.

Changing names

For the most part of its history, the geographical boundary of present day Vietnam covered 3 ethnically distinct nations: a Vietnamese nation, a Cham nation, and a part of the Khmer Empire.

The Viet nation originated in the Red River Delta in present day northern Vietnam and expanded over its history to the current boundary. It went through a lot of name changes, with Đại Việt being used the longest. Below is a summary of names:

| Period | Country Name | Time Frame | Boundary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hồng Bàng Dynasty | Văn Lang | Before 258 BC | No accurate record on its boundary. Some legends claim that its northern boundary might reach the Yangtze River. However, most modern history textbooks in Vietnam only claim the Red River Delta as the home of the Lạc Việt culture. |

| Thục Dynasty | Âu Lạc | 258 BC - 207 BC | Red River delta and its adjoining north and west mountain regions. |

| Triệu Dynasty | Nam Việt | 207 BC - 111 BC | Âu Lạc, Guangdong, and Guangxi. |

| Chinese Han Domination | Giao Chỉ (Jiao Zhi) | 111 BC - 544 AD | Present-day north and north-central of Vietnam

(southern border expanded down to the Ma River and Ca River delta). |

| Subsequent Chinese Dynasties | Commonly called Giao Châu.

Vạn Xuân during half-century independence of Anterior Lý Dynasty. Officially named An Nam by Chinese Tang Dynasty since 679 CE. |

544 AD - 967 AD | Same as above. |

| Đinh and Anterior Lê Dynasty | Đại Cồ Việt | 967 AD - 1009 AD | Same as above. |

| Lý and Trần Dynasty | Đại Việt | 1010 AD - 1400 AD | Southern border expanded down to present-day Huế area. |

| Hồ Dynasty | Đại Ngu | 1400 AD - 1407 AD | Same as above. |

| Lê, Mạc, Trịnh–Nguyễn Lords, Tây Sơn Dynasty | Đại Việt | 1428 AD - 1802 AD | Gradually expanded to the boundary of present day Vietnam. |

| Nguyễn Dynasty | Việt Nam | 1802 AD - 1887 AD | Present-day Vietnam plus some occupied territories in Laos and Cambodia. |

| French Colony | French Indochina, consisting of Cochinchina (southern Vietnam), Annam (central Vietnam), Tonkin (northern Vietnam), Cambodia, and Laos | 1887 AD - 1945 AD | Present-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. |

| Independence | Việt Nam (with variances such as Democratic Republic of Vietnam, State of Vietnam, Republic of Vietnam, Socialist Republic of Vietnam) | Democratic Republic of Vietnam (1945–1976),

State of Vietnam (1949–1956), Republic of Vietnam (1956–1975 in South Vietnam), Socialist Republic of Vietnam (1976–present) |

Present-day Vietnam. |

Almost all Vietnamese dynasties are named after the king's family name, unlike the Chinese dynasties, whose names are dictated by the dynasty founders and often used as the country's name.

It is still a matter of debate whether the Hồng Bàng Dynasty was real or just a symbolic dynasty to represent the Lạc Việt nation before recorded history. The Thục, Triệu, Anterior Lý, Ngô, Đinh, Anterior Lê, Lý, Trần, Hồ, Lê, Mạc, Tây Sơn, and Nguyễn are usually regarded by historians as formal dynasties. Nguyễn Huệ's "Tây Sơn Dynasty" is rather a name created by historians to avoid confusion with Nguyễn Anh's Nguyễn Dynasty.

See also

- Economic history of Vietnam

- Prime Minister of Vietnam

- North Vietnamese invasion of Laos

- History of China-detailed map animation of Vietnamese territories occupied by China throughout the past.

References

- ↑ Kenny, Henry J. (2002). Shadow of the Dragon: Vietnam's Continuing Struggle with China and the Implications for U.S. Foreign Policy. pp. 21.

- ↑ Neher, Clark D.; Ross Marlay (1995). Democracy and Development in Southeast Asia: The Winds of Change. pp. 162.

- ↑ Gerd Albrecht: Circular Earthwork Krek 52/62: Recent Research of the Prehistory of Cambodia PDF link

- ↑ Davidson, Jeremy H. C. S.; H. L. Shorto (1991). Austroasiatic Languages: Essays in Honour of H.L. Shorto. pp. 95.

- ↑ "Japan's Role in the Vietnamese Starvation of 1944-45 by Bui Minh Dung Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Jul., 1995), pp. 573-618 This article consists of 46 page(s)". Cambridge University Press. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0026-749X(199507)29%3A3%3C573%3AJRITVS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2.

- ↑ Neale, Jonathan The American War, page 18-19, ISBN 1898876673

- ↑ Neale, Jonathan The American War, page 18, ISBN 1898876673

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kolko, Gabriel Anatomy of War, page 36, ISBN 1898876673

- ↑ Neale, Jonathan The American War, page 19, ISBN 1898876673

- ↑ Neale, Jonathan The American War, page 20, ISBN 1898876673

- ↑ Neale, Jonathan The American War, page 23-24 ISBN 1898876673

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. ABC-CLIO. pp. 366. ISBN 1-57607-040-0.

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A history. Penguin Books. pp. 239. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- ↑ Hammer, Ellen J. (1987). A Death in November. E. P. Dutton. pp. 154–155. ISBN 0-525-24210-4.

- ↑ Clodfelter, Michael. Vietnam in Military Statistics: A History of the Indochina Wars, 1772–1991 (McFarland & Co., Jefferson, North Carolina, 1995) ISBN 0786400277.

Further reading

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." 2nd Draft Edition. [1]

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 AD. Draft annotated English translation. [2]

- Mesny, William. 1884. Tungking. Noronha & Co., Hong Kong.

- Nguyễn Khắc Viện 1999 . Vietnam - A Long History. Hanoi, Thế Giới Publishers.

- Stevens, Keith. 1996. "A Jersey Adventurer in China: Gun Runner, Customs Officer, and Business Entrepreneur and General in the Chinese Imperial Army. 1842-1919." Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 32 (1992). Published in 1996.

- Francis Fitzgerald. 1972. Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. Little, Brown and Company.

- Hung, Hoang Duy. 2005. A Common Quest for Vietnam's Future. Viet Long Publishing.

- The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2000. The State of The World's Refugees 2000: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action - Chapter 4: Flight from Indochina (PDF). [3]

- Lê Văn Hưu & Ngô Sĩ Liên. Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư.

- Trần Trọng Kim. Việt Nam Sử Lược. Trung Tâm Học Liệu 1971.

- Phạm Văn Sơn. Việt Sử Toàn Thư.

- Taylor, Keith W. The Birth Of Vietnam.

- Trần Dân Tiên. Những Mẫu Chuyện Về Đời Hoạt Động Của Hồ Chủ Tịch.

- Văn Tiến Dũng. Đại Thắng Mùa Xuân.

- Bui Diem. In The Jaws Of History.

- Nguyen Tien Hung, Jerrold L. Schecter. The Palace File.

- Phạm Huấn. Cuộc Triệt Thoái Cao Nguyên 1975.

- Hành Trình Biển Đông Vol 1 and 2. Anthology of memoirs by Vietnamese boat people.

- Nguyễn Khắc Ngữ. Nguồn Gốc Dân Tộc Việt Nam. Nhóm Nghiên Cứu Sử Địa.

- Văn Phố Hoàng Đống. Niên Biểu Lịch Sử Việt Nam Thời Kỳ 1945-1975. Đại Nam 2003.

- Lê Duẩn. Đề Cương Cách Mạng Miền Nam.

- Nhat Tien, Duong Phuc, Vu Thanh Thuy. Pirates in the Gulf of Siam.

- Nguyễn Văn Huy, Tìm hiểu cộng đồng người Chăm tại Việt Nam.

External links

- Vietnam History from ancient time

- Vietnam Chronology World History Database

- Viet Nam's Early History & Legends by C.N. Le (Asian Nation - The Landscape of Asian America)

- Tungking by William Mesny

- Pre-Colonial Vietnam by Ernest Bolt (University of Richmond)

- Human Rights in Vietnam 2006 (Human Rights Watch)

- French IndoChina Entry in a 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia about Indochina (New Advent).

- Virtual Vietnam Archive Exhaustive collection of Vietnam related documents (Texas Tech University)

- Geneva Accords of 1954 Text of the 1954 Accords by Vincent Ferraro (Mount Holyoke College)

- Việt-Học Thư-Quán - Institute of Vietnamese Studies - Viện Việt Học Many pdfs of Vietnamese history books

- Vietnam Dragons and Legends Vietnamese history and culture by Dang Tuan.

- Indochina - History links for French involvement in Indochina, casahistoria.net

- Vietnam - History links for US involvement in Indochina, casahistoria.net

- Early History of Vietnam - Origin of Vietnam name

- The American War: the U.S. in Vietnam - a Pinky Show online documentary video that includes a brief history of Vietnam

- Hoàng Văn Chí, Từ Thực Dân Đến Cộng Sản

- Hoàng Văn Hoan, Giọt Nước Trong Biển Cả

- Hoàng Văn Chí, Trăm Hoa Đua Nở Trên Đất Bắc

- Nguyễn Thanh Giang, Tưởng Niệm Con Đường Phan Chu Trinh

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||